Mandatory Participation Series Contents

It’s wrong for anyone to come between another person and the resources they need to survive. No person or group has the moral authority to impose conditions on anyone else’s access to the resources they need to survive.

But that’s exactly what we do. Our rules grant control of most of the Earth’s resources and the stuff we make out of them to a privileged few. Everyone else has to buy access to external assets from that group, or they won’t last long.

Because our system denies the vast majority of people access to enough resources to produce food, shelter, clothing, and the other things humans need for themselves, we are all owed at least enough cash compensation to buy them.

In some ways, it’s hard to believe the position I stated is controversial. Humans are the only animal that has to ask permission to use the Earth’s resources. Carnivores don’t have to ask permission to hunt. Herbivores don’t have to ask permission to graze. Plants don’t have to ask permission to photosynthesize. For most of the time humans have been on this planet, we didn’t have to ask permission either. But over the last few hundred years, the resources of the Earth have been divided into private property, and most of us didn’t get a share. Instead, we got an unofficial but very effective obligation to work for those who got shares. And for the most part, we’ve mistaken that starting point for our natural condition.

People will say that work is a fact of life, but that’s not true in the way we use “work” today. “Work” in the sense of toil to convert resources into consumption might be a fact of nature, but “work” in the sense of spending time making money by providing services for people who have money so you can get permission to access resources is entirely the result of the rules that have been imposed on us.

UBI is both compensation for interference with our efforts to provide for ourselves and protection from deprivation. A substantial UBI removes the underlying threat of deprivation we use to effectively force people to participate in our economy and creates a kind and humane society based on positive rewards to elicit genuinely voluntary participation.

One common but phony defense of the mandatory-participation economy is to deny that it exists by claiming we all have the option of “self-employment,” which sounds much freer than it is. Self-employed people need clients, landlords, and banks, or their work is for nothing. Self-employed people might not take direct orders, but they serve resource owners as much as anyone else. If they refuse, they’ll eventually find themselves with no capital to work with, no shelter to sleep in, and no food to eat.

Our phrase for someone who doesn’t have to work for the people who control property is not “self-employed” but “independently wealthy.” That is, the only way you can be free from the need to provide services for property owners is to become one of them—and most of us never will.

Another spurious defense of the mandatory-participation economy—and of inequality in general—is to deny the role of resources and to attribute all inequality to value created by owners. People can create inequality of wealth without depriving anyone of resource access if they increase the economic value of the resources they have while other people retain access to their share resources. That can and does happen, but it’s a poor explanation of why most inequality exists today and why so many people are born and live their whole lives without independent access to enough resources to keep them alive. Just the land in our cities is expensive beyond the reach of all but the wealthy few. If we wanted to embody the ideal in which people who own wealth do not deprive others of resources, we would need some universal policy, like UBI, to ensure everyone does, in fact, have legal access to the resources they need to survive and thrive.

Two simple and obvious facts, often ignored in political debate, are that human beings need resources to live and that all goods are made at least partly out of resources. You can’t write computer code without a computer, electricity, an apartment or an office, and generations of past technology. Resources we all need to survive are owned by a small number of people. You have to get the owners to part with their resources voluntarily. The only legal way to do that without begging is to provide some service for them.

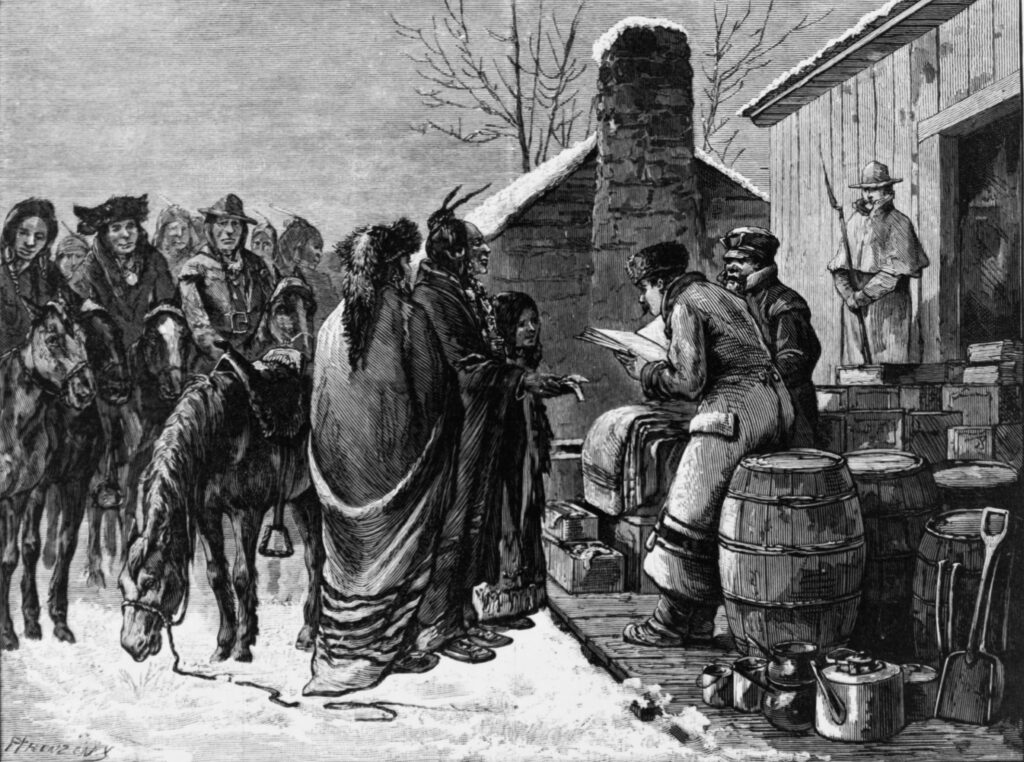

Freed slaves at the end of the civil war knew this. That’s why one of their spokespersons, Garrison Frazier, asked General Sherman for 40 acres and a mule. Unfortunately, the freedmen’s former masters knew it too. That’s why President Andrew Johnson—a former slaver—took back the land Sherman allocated to formerly enslaved people.

Our rules create poverty, homelessness, and economic destitution. We like to think of poverty as something that other people bring on themselves or as something that just happens. But in fact, poverty is a lack of legal access to the resources needed to survive and thrive. The only reason you can lack legal access to resources is that the law says somebody else controls them, and you don’t. Hunter-gatherers and subsistence farmers might have difficult lives in many ways, but most have fulfilling social lives; none of them are homeless; none lack legal access to the resources they need to survive; none lack the ability to provide their own food by their own efforts without following anyone’s orders; no one equates “work” with following someone else’s orders.

Rules that say a few people own resources essential for everyone else’s survival put the vast majority of us (90%, perhaps 99%, of us) in a position where we have to work directly or indirectly for someone in the group that controls resources. They won’t jail us if we don’t, but they will send us back to the contemporary economy’s default position: economic destitution. If you have a good job and good prospects, your starting point fades into the background, but it is always there, acting as a threat to keep you and me working for the wages the people who control resources want to pay.

A false response to my argument is to deny that there is any force in the system because no single employer forces any single employee to work for them. The business owner simply offers employment. This is true at the individual level, but you have to think about the system. The problem is not any individual’s behavior. The problem is the rules of the system. If the rules say some people own resources and others don’t, the rules effectively force members of one group to work for at least one member of the other group. Whatever else you think of the private property system, it has that effect unless property owners compensate the propertyless with some universal program like UBI.

The ability to refuse any one employer is better than chattel slavery, but a choice of masters is not full freedom. Freedom is independence, the power to say no to any and all masters if one so chooses. We might exercise that freedom by doing something other than paid labor; we might use it to bargain for better wages and working conditions within the paid-labor system; we might use it to learn better skills and reenter the market in a way that makes a bigger contribution and receives a bigger reward; or we might decide we’re happy doing what we’re doing right now. But whatever we do, it will be an unforced choice, not one made to avoid the threat of destitution.

So, this essential argument includes many elements: we shouldn’t have poverty and economic destitution, or at least we shouldn’t create it. We shouldn’t use destitution as a threat. By doing so, we threaten the freedom of the vast majority of people, forcing them to accept lower wages and less attractive working conditions than they might command if they had the power to say no to the jobs on offer. This system cruelly and needlessly forces just about everyone to live with the underlying anxiety that they might one day fall into poverty and economic destitution.

I call this an “indepentarian” argument for UBI because it stresses respect for each individual’s independence. It is “Painist” in the sense that it relies on the observation Thomas Paine made about our property system back in 1797.[i]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Most of the posts in this series were written with the intention of going into my forthcoming book, Universal Basic Income: Essential Knowledge for MIT Press, and many, if not most, of the ideas presented here did make it into the book, but the publisher suggest I soften the wording and some of the arguments, because as is, in this version of it, “the anti-UBI crowd seems like a bunch of mustache-twirling robber barons,” and she rightly thought that the antagonistic stance would be less convincing than more confrontational one here. So, for the book, I made those changes, but I liked what was left out as well. I thought there must be a place for it. And I decided that place was on my blog. I refer everyone to the book because it has a different approach; because it benefits from peer review, copyediting, and more extensive proofreading; and because it has important ideas that aren’t here. Also, many of the arguments here are developed more fully in other books and articles of mine, most of which you can find on my website: www.widerquist.com.

Karl Widerquist, Karl@Widerquist.com

[i] Paine, “Agrarian Justice.”

This article not only makes common sense but it reveal the only truth about human condition and how the privilege control the majority of the population to stay

poor…

It’s time for us to redeem our right…By demanding UBI which is due since from the first generation.