Jesús Aller recently published a review and summary of the Spanish translation of Grant McCall’s and my book, Prehistoria de la propiedad privada. Implicaciones para la teoría política contemporánea [The Prehistory of Private Property: Implications for Modern Political Theory]. Translated by Sara Ortega. The review appeared in Rebelión on August 25, 2023. A Google Translation of the review follows.

There is no stranger contrast in this world of ours than that which exists between the likeness of the anatomies and physiologies of human beings and their differences of heritage. Anyone can suspect that the abysmal inequalities observed in the latter aspect are neither reasonable nor beneficial to society as a whole, but the surprising thing about the case is that they have managed to convince us that private property is not only natural, but even sacred.

Is it really that? The issue is arduous, but an important first point to clarify the picture is to analyze with a temporary perspective that includes prehistory, whether the forms of ownership that are dominant today were also in the past. Since Piotr Kropotkin’s pioneering contribution in Mutual Support (1902), many have been concerned about this problem and the bibliography in this regard is wide, but among the texts dedicated to it is one, recently edited by Bauplan, Prehistory of private property. Implications for contemporary political theory, which update anthropological and historical research on the subject and also rigorously discusses various theoretical aspects involved.

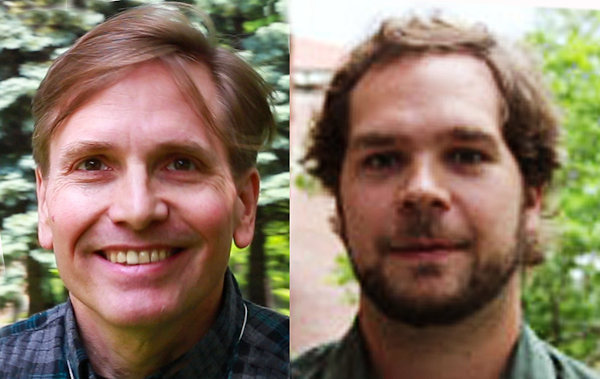

The authors of the volume are American professors Karl Widerquist, a political scientist and economist, and Grant S. McCall, an anthropologist, a very appropriate team to address this issue. His joint work has already led to another previous book: Prehistoric Myths in Modern Political Philosophy (2017), in which he skilfully argues against the liberal assumption that societies in capitalist states are more beneficial to people than small non-state societies.

In their new book, which has been put in Spanish by Sara Ortega, Widerquist and McCall dedicate a first section to assessing the widespread claim that inequality is natural and inevitable if we do not wish to renounce freedom. The second section studies whether capitalism is more respectful of freedom than any other economic system, and the third and more extensive, analyzes the crucial problem of private property through a journey through human history.

A Historical Approach to Inequality

The establishment of hierarchies and the emergence of inequality in societies can be seen from prehistory, and is always based on an ideology that considers natural and inevitable segregation, while attributing it to varied reasons, such as the intellectual, moral or genetic superiority of the upper class and even the divine character of leaders. The division also expresses a willingness to reward services to society or the idea that only hierarchies are capable of maintaining peace.

In contemporary social sciences and political philosophy, the belief in natural inequality survives, and is often defended as inevitable and coercive rules are justified that maintain it, although the explanations given on the basis of social differences do not resist critical analysis. The difficulty of a theoretical study of this question advises a review of the human past in search of dominant patterns and this is what Widerquist and McCall do.

In this sense, the evidence gathered in the book completely refutes the inevitable nature of inequality, by showing very high levels of social, political and economic equality, both in land tenure and in property systems, in a wide variety of societies studied by prehistorators, historians and anthropologists. These are groups active for extremely long periods of time and able to protect the freedom of their individuals at least as well, if not better, than companies based on property rights. It is therefore fallacious to defend inequality in the name of freedom.

The freedom of capitalist society under review

Contemporary thinking dominates the idea that capitalism offers individuals a freedom from the impositions of the rest of society (negative freedom) greater than that granted by any other system. However, so far this statement has not been theoretically substantiated in a consistent manner, as the many and varied cuts in freedoms imposed by the private property regime are ignored. The difficulty of a theoretical analysis that is seen again in this case advises again to address the problem empirically.

The construction of the precise argument is proposed in the book through an examination of the economies of various hunter-gatherer societies, which shows that these are more consistent with negative freedom than the market economy. Although freedom is certainly difficult to measure, it is greater in the people of the peoples studied than in the less free of capitalist societies. In fact, there is no form of coercion or aggression to which hunter-gatherers are subject and to which the lower and middle classes of capitalist society have been released.

The analysis therefore leads to the conclusion that the market economy, as commonly conceived, does not offer maximum egalitarian freedom. The supposed superiority of capitalist societies cannot be based on the claim that they promote negative freedom.

Private property: rare avis in the long history of humanity

The authors call the hypothesis of individual appropriation – the set of justifications, based on supposed rights, which seek to inform the systems in which inequality exists. These justifications rest on the principle that private property is natural and collective ownership systems tend to be established only in very particular cases. It analyzes the emergence of this hypothesis in the 17th century and how its influence extends until it becomes a background assumption of contemporary political theory.

After evaluating attempts to settle private property rights on an a priori basis and demonstrating their lack of solidity, the authors present a series of evidences that can solve the problem through a tour of the various stages of human prehistory and history. First, it is found that the nomadic societies of hunter-gatherers appropriated most of the planet, but in contradiction to the hypothesis of individual appropriation, they chose not to establish private or land property, which was and is common to them, or on food or tools, shared in many cases.

With the advent of the Neolithic, the first farmers are often considered to have introduced private land-owned systems and this assumption is used to support private ownership as a natural development. However, the evidence presented in the book shows that this is not the case, but that private property originated long after agriculture. The fact is that individual appropriation plays no role in the most primitive agricultural communities, which operate on a small scale. What is observed in them is a community system, both at work and in the distribution of harvest and nothing like the supposedly natural individual appropriation system.

When the states form, land tenure systems emerge in which political elites, kings or pharaohs were considered owners of the entire size of their realms and the subjects had various usufruct rights for agriculture or other practices. The beginnings of individual private property occurred gradually, long after the formation of the states, and not through individual appropriations, but because of the activity of elites who used their political power to appoint themselves or their subordinates as owners. However, it must be said that even then, private ownership of land did not become the dominant property rights system, and this is true for both the Ancient and Middle Ages, times when communal village farming remained the most frequent system in state societies around the world.

Private property: Poisoned gift of Modernity

Once it has been shown that private property is a rarity throughout human history until very recently, the question that arises is how this system that has become dominant spread throughout the world. Widerquist and McCall analyze the two processes that in their opinion are responsible for the great change and that operate from the 16th century: the fences (enclosures), which begin in England extend through Western Europe and impose individual property in rural areas, and the waves of settlers from this continent who established all over the orbity of property rights of the land outside local traditions. The fences and colonial movements were coercive and violent processes, but it is important to emphasize that they did not limit themselves to stealing property all over the world, but that beyond this they imposed a new private property system on people who had hitherto known communal ways of life.

The evolution described above can be synthesized by saying that human beings who began to settle and practice agriculture established complex land tenure systems, but with a collective in many cases, and with important common elements. In this way, the hypothesis of individual appropriation – that was tested, not only is not demonstrated, but is refuted. The above-mentioned story indicates that the establishment of privately owned systems necessarily implies coercion and violence, so that the thesis that the defense of unequal private property is somehow the defense of natural freedom – lacks basis.

Arguments to get out of the maze

Prehistory of private property rigs with rigor three solidly established beliefs in our world about the system of private property dominant in it and that serves as the foundation for the capitalist system. It is shown first of all that inequality is not natural and inevitable and that equality is compatible with freedom. Secondly, it is clear that capitalism is no more consistent with negative freedom than any other conceivable economic system. Finally, it is clear that the dominance of the private property system is a newcomer to our history.

Those of us who defend the old slogan that Another world is possible are overwhelmed many times by how everything around us seems to be a palpable demonstration of solidarity and mutual support are entelequias with no connection to the current reality of the human being. The great merit of Karl Widerquist and Grant S. McCall with this book is to make clear, for anyone sensitive to data and arguments, two crucial facts about private property. First of all, in the two hundred thousand years that Homo sapiens has been on the planet, this was not until very recently the dominant norm we see today. And secondly, that in no way individual appropriation is a guarantee for freedom, but rather the opposite.

—

Jesús Aller (Gijón, 1956) is a professor of Geology at the University of Oviedo and writer. In this last aspect he is the author of Poesía (1980-1990), Asía, alma y laberinto (2002), Recuerda (2004) y Subhuti (2006), the last three books published by the publishing house gijonesa Llibros del Pexe. More information about his literary activity can be found found on his personal page: http://www.jesusaller.com